And the Winner Is… Social Connection?

- Donatella Massai

- Oct 31, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2025

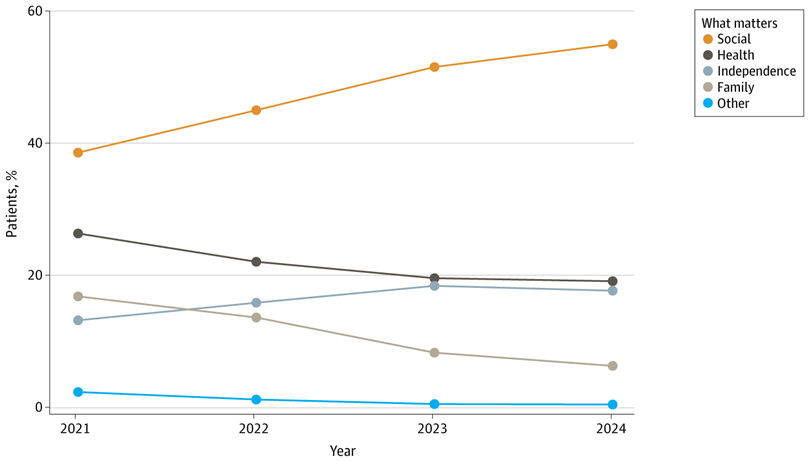

I have read for you a fascinating set of reflections on what truly matters for a long and meaningful life. A large-scale study published in JAMA Network Open (2025) conducted across the United States asked more than 388,000 adults what matters most in life.

Nearly half of participants (48.6%) identified social activities and inclusiveness as their top priority, more than twice as many as those who ranked health first. It is not only showing the importance of connection, it also reveals a shift from family ties toward a broader sense of community and belonging. Across age, gender, and ethnicity, the message seems unmistakable: people want to feel part of something larger than themselves, not simply to live longer on their own.

This finding adds a new dimension to how we understand living well. Balance among the seven pillars of longevity remains essential, as I often write about in this blog. Yet studies like this remind us how much our wellbeing depends on the quality of our social lives, the people with whom we share time, laughter, and mutual care.

I see this in my research on social frailty, which looks at how social ties evolve as we age. Our networks can quietly thin out, becoming less diverse and less deep. We also know that social isolation is associated with a higher risk of chronic diseases and with increased mortality.

We live longer, yes, but often more alone. Our lives have become organized around efficiency, privacy, and self-reliance. Yet what sustains us, in the end, is interdependence, the quiet strength that grows when care, purpose, and the small stories of our days are shared with someone who truly listens.

“One of the marvelous things about community is that it enables us to welcome and help people in a way we could not as individuals.” — Jean Vanier

I thought about this while reading Louise Perry’s essay It’s Not Normal to Raise Children Like This. She writes about modern motherhood as something increasingly private, managed alone rather than supported by a wider circle. The exhaustion and anxiety she describes are not personal failings but the predictable outcome of a social model that expects individuals to do what once required a village.

I know this feeling well. Raising two children abroad meant living without a community around us. I tried to give them some stability, to let them grow their roots in Europe, especially in Italy. My daughter Calypso was born in Brussels, and my son Dimitri in Rome. While protecting them from constant travel, I kept moving, even if for short periods of time: Turkey, Somalia, Zanzibar, Nicaragua, Peru, Brazil, Haiti, Senegal, Chad. Those years taught me resilience, but also the limits of doing it alone.

Perry writes about our longing for community through examples of people who are reimagining how to live together. She mentions initiatives such as Live Near Friends, a platform that helps people buy homes close to one another to foster everyday connection. Similar experiments are emerging elsewhere, like this women’s co-living community in New York and a cooperative house shared by 26 women in England, These communities are built on trust, reciprocity, and shared care. As Perry writes, they reveal both our hunger for connection and the challenge of interdependence: If you want a village, you have to be willing to act as a villager.

The same idea resonates in Ken Stern’s book Healthy to 100, where he writes that the secret to living longer is not found only in nutrition, exercise, or medical care, but in the strength of our relationships and the social fabric around us. In places such as Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Spain, he shows how intergenerational bonds and shared purpose shape healthier, longer lives. His words echo what both research and experience tell us: longevity grows where connection thrives.

Social connection may not be the whole story of a long life, but it is the part we too easily overlook. This is where a vital part of longevity begins, not only in perfect diets or daily metrics but in the often-neglected work of rebuilding proximity, reciprocity, and presence.

Maybe it is time we explore the possibility of living differently, shifting our priorities, rediscovering shared spaces, and rebuilding communities where we can find what we did not know we were missing.

The study offered one answer. I’m curious to know yours:

If you were asked what matters most to you, health or social connection, what would you choose today?

0%Health

0%Social connection

Comments